Photo of the week

Highlight of the week: A very close encounter with an elephant

Lowlight of the week: A very close encounter with an elephant

Maximum temperature: 36 degrees Celsius

Rainfall: Not yet

Malaria. The disease that has historically kept Africa African. The scourge of explorers, missionaries and adventurers. Literally, malaria means bad air. Thought to be transmitted by bad air from the swamps. The swamps where the anopheles mosquito breeds. But bad air was not the problem. Merely a by-product of the perfect storm of mosquitoes, plasmodium parasites and people.

Malaria today is an exotic disease almost never seen in Britain. But only a century ago the South of England had its fair share. It fascinates British doctors. Each imported patient with malaria is usually quizzed to death by medics. Eager to know its presentation. A kudos diagnosis. Not to be missed. A problem that we deal with daily in our basic primary health centre in Zambia. It can only be treated by Professors of Tropical Medicine in tertiary referral centres in Britain.

Keith and I have already had more than our fair share of malaria. Well, Keith has. He was struck down 3 times whilst we lived and worked in Tanzania. The first episode was a never to be forgotten affair. He also had bilateral pneumonia. Like a sketch from Not the Nine O’clock News: Keith’s collection of illnesses competed to justify him a hospital bed. But Keith declined admission and opted for one-to-one care in our own house. Our house was in the sticks in Zanzibar. It was terrifying for me. I was his nurse and his doctor. His next two episodes of malaria were no worse than mild flu. In comparison, my single episode was a minor blot on the landscape. I barely raised a fever. I had a slight headache. And of course, we both lived to tell the tale.

Currently in Zambia, malaria is the number 5 killer. HIV, neonatal conditions, pneumonia and stroke kill more Zambians than malaria. Crikey. I feel a familiar rant coming on. Malaria is behind stroke in the causes of death in Zambia! But malaria receives way more funding. Are strokes not sexy enough?

But I digress. Let me stick to ranting about malaria for now. Malaria deaths have reduced massively over the past 20 years. In fact, the numbers have halved. Mosquito nets. Rapid testing. Better drugs. Better general nutrition. Malaria prevention and care has come a long way. But we should not rest on our laurels. A massive upsurge in cases is likely just around the corner. Unless things start to change now.

But first, a bit of parasitology. Malaria. There are 5 different types. The killer here in Zambia is falciparum. Falciparum malaria kills because the parasite can make the red blood cells stick to the blood vessels. Infested red blood cells are sequestered. If all the blood cells stick to the lining of blood vessels and to each other, they form mini clots. Not so good in the brain. Or in the kidneys. Or in the lungs for that matter.

Because infested blood cells are not circulating, the spleen does not remove them either. The spleen’s main job is side-lined. And so, parasites are allowed to sit in their clots. The falciparum parasites party and divide. A massive malaria factory. Deep in the body. Eventually the brain swells. The kidneys pack in. The lungs stop oxygenating. And death is a blessed relief.

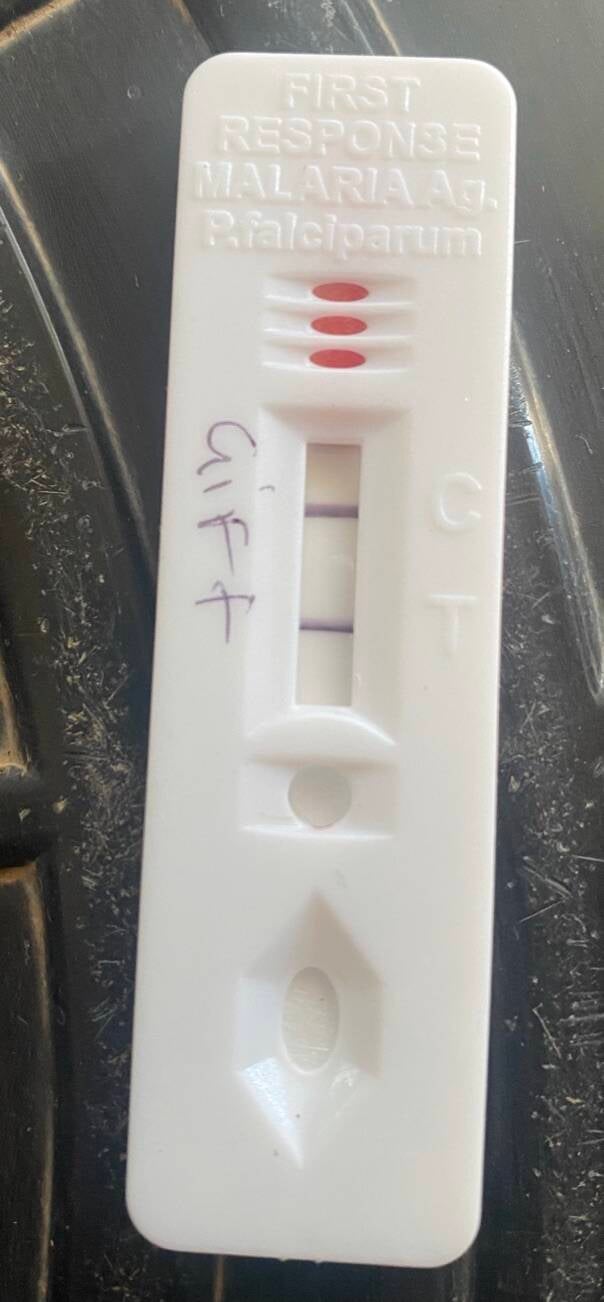

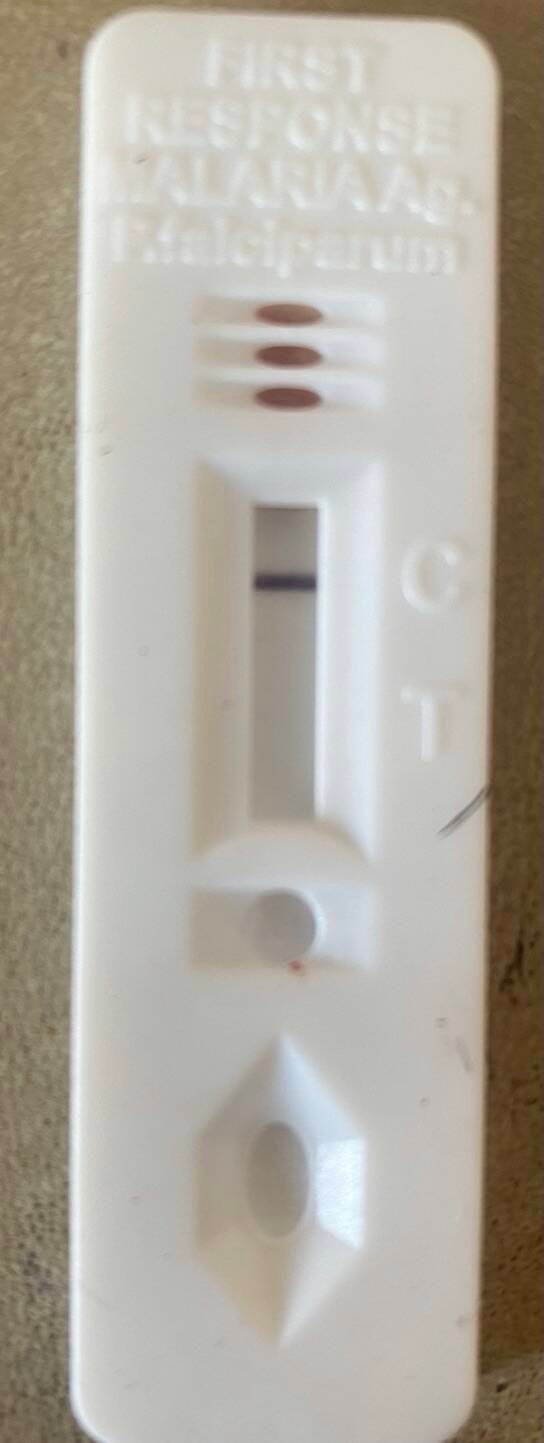

Yet, this chain reaction is unnecessary. Malaria produces symptoms. Fever. Body aches and pains. Headache. Fatigue. Vomiting. The list goes on. A test for malaria is available. An RDT. A Rapid Diagnostic Test. From a single, small, drop of blood. Rather like the COVID tests we all got so used to 3 years ago. The result is available in 10 minutes. It can be done by amateurs. A brave soul pricks a finger. For that all important drop of blood.

If no RDTs are available, a blood slide must be done. This takes skill. Time. Equipment. Electricity. A drop of blood is placed on a glass slide. It is spread skilfully across the slide. A technician makes both a thin and a thick film. Tricky. A skill that needs to be taught and refined. I tried this a few times. In Glasgow last year. Studying for my diploma in tropical medicine and hygiene. A 3-day microscopy course taught me the basics. It takes 90 minutes to prepare the films. And an experienced eye to read the slides. Even then, our microscope needs power. All the ducks need to be lined up in a row.

So, how can we stop this awful disease? Our first option is to avoid that mosquito bite. Not just any old mosquito bite. The anopheles mosquito bite. Only the females bite. Their maternal instinct is strong. They need a blood meal for their brood. The female suckers bite at dawn and dusk. And during the night. The plasmodium parasite an accidental hitchhiker. Avoiding female mosquitos is easier said than done. It’s not a simple matter of Just saying No. My ankles and thighs are currently a mass of bites. Even though I spray on DEET and cover up. My bum gets bitten when I go to the toilet. My ankles when I forget to re-spray. Mama mosquito is a wily adversary.

A mosquito net protects us at night. An effective defence. But not perfect. Tinnitus or a teasing skitter? Your ear buzzes just the same. Choose your torture. If a skitter penetrates our shield, our whole night is ruined. The search lights come out. We recreate the Blitz and send off volleys of swats into the night air. Ack-ack guns or plastic swats.

All Zambian mothers are given a new mosquito net when their infant reaches 9 months of age. Maternal antibodies to malaria and measles wane in the baby at that time. We seize the perfect opportunity to give the first measles jab. And in the spirit of thrift, we provide a buy one get one free deal. Mum and babe receive a net into the bargain. The baby’s tears of pain are matched by the mother’s tears of joy at the prospect of a peaceful night’s sleep. Our under-tree clinics are popular and effective. We are yet to see measles in Zambia and we’ve never witnessed a child death from malaria.

However, not everyone seems convinced of the value of a peaceful night’s sleep, and the knock-on benefit of saving lives. These mosquito nets also have a covert value. We see the nets transformed and used in the Luangwa River. The nets can sell for a few kwacha to our local fishermen. Mosquito nets catch fish in our crocodile infested river. Adding insult to injury, these fine nets do not discriminate between baby fish and older fish. The eco system and our vulnerable children are both on the losing side of this worrying trade.

Travellers are rightly circumspect of malaria. Most take a second option of defence. Anti-malarial tablets. Very effective. The choice depends on budget and tolerance. We are often called to travellers with worrying symptoms. The fear of malaria appropriate. But mistimed. Malaria’s incubation period is at least 8-10 days. These travellers will not succumb here in Zambia. Their tablets worthwhile. But designed to save their own doctors the headache of an exotic diagnosis nearer home.

Our safari guests have often picked up the flu or another virus on their flight. These fevers too early to be their worst fear. We get kudos for our knowledge of the parasite’s natural history. Usually, no malaria test is wasted. We see plenty of malaria here but never in our short-term tourists.

Treatment is the final link to our lifesaving chain. Provided malaria is picked up early the treatment is easy. 3 days’ worth of Co-Artem tablets. Well tolerated. Very effective. Injectable Artesunate reserved for severe infections and those in mortal danger.

So, why is this blog titled Rationing? This year, malaria tests are proving a challenge.

Rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) are currently in short supply. Our diagnostic plan B is also under enormous pressure. Glass slides are hard to come by. Electricity as rare as hen’s teeth. Thankfully we have an ever-resourceful lab team. They wash the slides carefully after each use. Their microscope is buddied up with a solar power generator. The sun never fails around here. Not during the day at least. Our ducks are all in a row for now.

In previous years we have been awash with RDTs. In the clinic. In the community. Community leaders are trained to do the tests. Co-Artem is also available in the community. No need to walk 10 km to our clinic with a feverish sick child. Or an adult for that matter. Consequently, our district rarely sees serious cases or deaths.

But now in Kakumbi malaria tests are strictly rationed. A discipline that challenges staff only trained to recognise possibilities. Diagnostic acumen comes with experience, and all of our staff are under 30. In our late 50s, we are now able to discriminate. Who to test? Who to treat?

For now, our staff may only treat when they have a positive malaria test. But they are not allowed to test unless they can convince the lab team to use a precious RDT. Or a time consuming slide. Out of hours the lab staff are off duty and a single RDT is under the lock and key guard of the lead clinician.

So, rules are rules. Imagine the harsh realities of a night on call:

It's 23:00 hours. A 2 year old child is brought to clinic. Seriously unwell. She is barely conscious. Her temperature is 39 degrees Celsius. She is breathing fast. Her mother reports that she has had a short seizure. There is a diagnostic dilemma. Is this a simple febrile convulsion due to a virus? Frightening for all to see. Harmless. Self-limiting. Needing no specific treatment. Just a watchful eye.

Or perhaps this child has meningitis? Much more serious. Deserving of antibiotics. And a very close eye.

Even worse, she might have cerebral malaria. Cerebral malaria may cause irreversible brain damage. Death is likely if the illness is not treated aggressively.

But you are the clinician on duty. You can’t just give intravenous artesunate. You must have a positive test result first. There are no lab technicians working overnight. There is no electricity either for that matter. So it would be pointless to bring the lab staff in. Oh, and we have no RDTs left. So, you give the child antibiotics and wait until morning. At 08:00 the lab staff pitch up. But you have to wait for another 90 minutes until a result is forthcoming.

I thought we had malaria sussed out here. Previously any little tots with a fever have always had an RDT. So that we don’t miss malaria. Most tots being perennially snotty. But now that the supply chain has been breached, we have had to look inwards.

Our local Malaria Programme officer visited last week. He was horrified at our dilemma. He chose to externalise the blame. Despite daily requests, the district office denied culpability. Why were supplies not requested earlier? You just need to ask.

Despite continuing daily requests our RDTs are still under lock and key. Perhaps the clinic can do a handful a day. Who deserves the tests? Each patient is grilled and prodded. When influenza came to town a fortnight ago, the art of safety netting came to the fore. Bus loads of feverish people with any suggestion of a runny nose or cough have been turned away with a plan. A plan to come back if the fever fails to break

Our RDTs are mostly kept for the night shift. But still I fear that our morning arrival in clinic will be greeted with the wails of disconsolate relatives. Their child semi-conscious, or worse, because of an easily treatable foe. Fifty pence for a disposable RDT. A life? A death?

Update

We are pleased to report that Mary has finally got home. She is now recovering from her stroke and getting plenty of rehab. We wish her all the best.

Our very own pride of 13 lions

Highlight or lowlight? A bit too close for comfort

A more relaxing elephant encounter on our road home from work

RDTs. Child's play. Positive and Negative

Add comment

Comments

Fascinating insight into rationing. I guess world wide there will always be rationing issues of some sort affecting the delivery of good quality care. Nobody want to take the blame!

Love the elephant pictures. 🥰

What happened to the USAID anti malaria programme in 2020, which was going to eradicate the disease? Lack of funding?

Now we know why Keith was so persistent about anti malaria tablets when Mary and I visited Keith at his practice.

Great work guys , you're doing a wonderful job.

PS - watch out for those elephants

XX